Kalasha Style

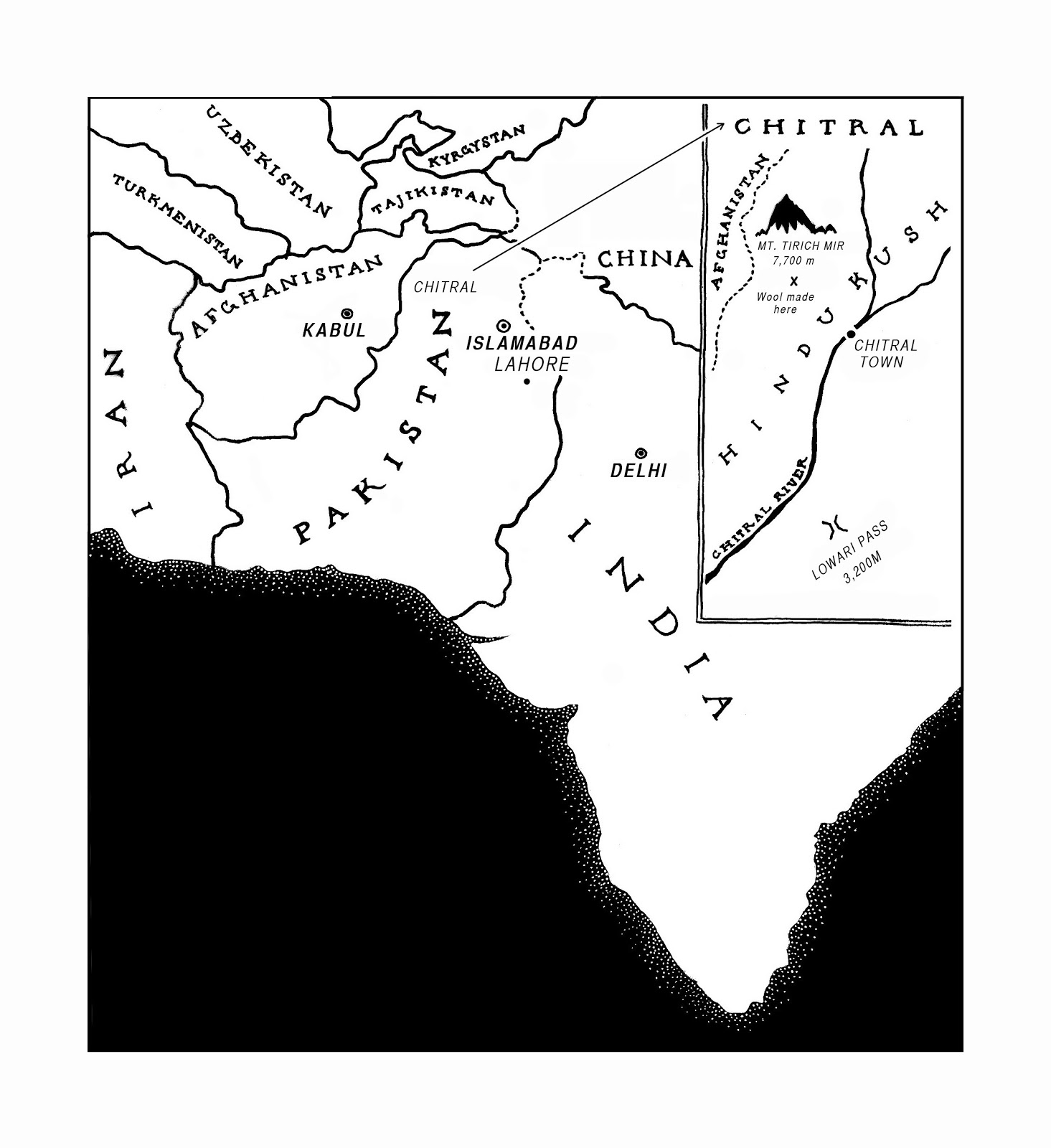

The most iconic garments from Chitral are the heavily embroidered dresses of Kalasha women. The Kalasha are a minority within Chitral, non Muslims who live in three small valleys on the border with Afghanistan. Their religion which includes elements of animism and polytheism, but which acknowledges one god, was once practiced across the Hindu Kush, but now is limited to 3,000 or so adherents.

The Kalasha's unique religion, their beautiful valleys, their distinctive costume and certain practices like wine making and solstice festivals have long made them popular with scholars and more recently; tourists. Throughout Pakistan and abroad the Kalasha have come to be symbolised by the striking dresses worn by their women. These dresses start off life as a baggy black cotton shirt, which is then personalised with bright wool embroidery around the hems and collar. Interestingly these dresses are a recent innovation. Traditionally Kalasha women wore brown-black homespun woolen dresses, globalization and the introduction of a monetary economy to the region have provided women with access to cheap cotton and dyed wool from China. Ironically enough it is the availability of mass produced products which has given Kalasha women a new means to express their individuality.

The photos below are of our friends or their relatives in Kraka village (2011).

Photos reproduced with kind permission of Matan Rochlitz.

The most iconic garments from Chitral are the heavily embroidered dresses of Kalasha women. The Kalasha are a minority within Chitral, non Muslims who live in three small valleys on the border with Afghanistan. Their religion which includes elements of animism and polytheism, but which acknowledges one god, was once practiced across the Hindu Kush, but now is limited to 3,000 or so adherents.

The Kalasha's unique religion, their beautiful valleys, their distinctive costume and certain practices like wine making and solstice festivals have long made them popular with scholars and more recently; tourists. Throughout Pakistan and abroad the Kalasha have come to be symbolised by the striking dresses worn by their women. These dresses start off life as a baggy black cotton shirt, which is then personalised with bright wool embroidery around the hems and collar. Interestingly these dresses are a recent innovation. Traditionally Kalasha women wore brown-black homespun woolen dresses, globalization and the introduction of a monetary economy to the region have provided women with access to cheap cotton and dyed wool from China. Ironically enough it is the availability of mass produced products which has given Kalasha women a new means to express their individuality.

The photos below are of our friends or their relatives in Kraka village (2011).